Biodiversity Summit COP15: Agreement on More Biodiversity Protection

In December 2022, more than 190 countries adopted the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework at a global biodiversity summit (COP 15). This is a landmark agreement that will steer the global action on biodiversity until 2030. While it is historic that countries were able to make an agreement in the first place, the content of it is on another page.

In December 2022, more than 190 countries adopted the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework at a global biodiversity summit (COP 15). This is a landmark agreement that will steer the global action on biodiversity until 2030.

There is no overstating this - this agreement is a historic moment for biodiversity that was four years in the making. The biodiversity summit, unlike its climate counterpart, only takes place once in a decade, which is why it was particularly important to agree on ambitious and urgent action. Especially because according to many experts we are in the middle of a mass extinction event, and knowing none of the biodiversity targets that were set for 2020 were reached, the pressure on decision-makers was high to get it right this time.

Adding to the pressure was the fact that the biodiversity summit was supposed to take place in 2020, but was repeatedly delayed due to COVID-19, and negotiations were very difficult throughout, leaving many concerned about the possibility of not getting an agreement at all, which would have been disastrous, knowing how important it is to finally take effective action on biodiversity in this decade.

Was was agreed on at the summit?

Countries that signed on to the agreement committed to:

- effectively conserve and manage at least 30% of the terrestrial areas, inland water, and coastal and marine waters by 2030

- ensure that by 2030 at least 30% of degraded terrestrial inland water and coastal and marine ecosystems are under effective restoration

- reduce pollution risks and the negative impact of pollution from all sources by 2030 to levels that are not harmful for biodiversity, including risk reduction from pesticides, as well as reducing losses from nutrients and plastic pollution

- identify and by 2025 eliminate, phase out of reform incentives, including subsidies, that are harmful to biodiversity

- set up a special trust fund to support the implementation of the Global Biodiversity Framework; with developed countries increasing total biodiversity-related international financial resources to at least 20 billion USD per year by 2025, and at least 30 billion USD per year by 2030

- report their progress towards meeting the targets via national biodiversity plans

- recognize and respect the rights of Indigenous peoples over their traditional territories, and ensure that Indigenous peoples have a voice in decision-making

What are the next steps?

While it is historic that countries were able to make an agreement in the first place, the content of it is on another page. The agreement on global biodiversity goals certainly is a step in the right direction, but as always, now it is up to governments in the different states to ensure that this agreement is actually implemented. With biodiversity loss happening at an alarming scale and speed, and with the ongoing climate crisis, the path we take in this decade will be decisive. It is a lot of responsibility, but the good news is that there is plenty of research and expertise to help guide us towards effective conservation and restoration of nature, and political leaders can learn from mistakes that were made at the last biodiversity summit.

To make this agreement a success, governments will have to ensure that the 30% protection target is implemented in practice. Designating an area as protected is only the first step - protected areas need to have management plans, and sufficient human and financial resources allocated to meaningful implementation of these management plans. Progress needs to be monitored, evaluated and management plans adapted as necessary. In designating protected areas, governments have to choose areas that are ecologically representative and well-connected; even if protecting those areas means a loss of profit for industries that benefit from overexploiting nature. In the long run, the cost of inaction on biodiversity is higher than the cost of protecting it.

Governments also need to ensure that there are no ambiguities that will lead to loopholes in implementation. Crucially, although countries have to report on progress towards reaching biodiversity targets, this framework is not legally binding. This is why countries who adopted the framework now have to swiftly incorporate and implement the goals in their own national legislation to make them binding. Furthermore, the 30% protection target allows ‘sustainable use’ of protected areas, and it is important to ensure that this does not lead to greenwashing, and that human activities that are allowed in protected areas do not interfere with the objective of allowing nature in those areas to recover and thrive. The language on harmful subsidies is also not explicit enough, as it is unclear whether those subsidies should be eliminated, phased out or reformed. Countries need to ensure that those subsidies are eliminated - this is the only way we can claim we are taking coherent action on biodiversity. We cannot commit to protect biodiversity on one hand, but then pour money into projects that destroy it. Finally, the rights of Indigenous peoples need to be respected on the ground, not only on paper.

What was agreed on ocean protection?

An important aspect of this framework is that unfortunately the oceans have not been at the forefront of discussions. Although the oceans are home to some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet, and although their role in weather regulation and oxygen production is crucial for life on Earth, the oceans are often not sufficiently included in biodiversity discussions.

When it comes to ocean protection, it is important to remember that most of the ocean surface lies outside of national jurisdiction, and protection of those areas requires an agreement between countries. The ongoing UN negotiations on a so-called ‘high seas treaty’ should tackle those areas, but the last round of treaty negotiations ended in failure. These negotiations are set to resume in March 2023, and they need to be effective this time.

Furthermore, it is crucial that world leaders tackle overfishing, set sustainable limits on fishing quotas, and to strengthen the control framework on illegal fishing. To move towards truly sustainable fishing, we also need to invest into low-impact fishing methods and move away from destructive fishing practices such as bottom trawling. It is also high time to put in place a global moratorium on deep sea mining.

We welcome this agreement, especially in light of the very difficult negotiation process, and we will keep a close eye on its implementation. The EU should take a lead in putting biodiversity protection measures into practice and consider biodiversity protection in every political decision.

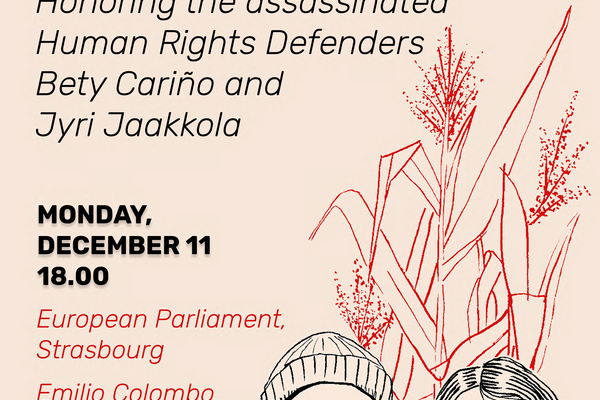

![[Translate to English:] Zeichnung von einem Mann und einer Frau mit der Überschrift Bety y Jyri.](/fileadmin/_processed_/5/1/csm_230614_BetyJyri-Website_96cba086d2.jpg)